This book is all about looking at the world around us and developing ways to simulate it with code. In this first part of the book, I’ll start by looking at basic physics: how an apple falls from a tree, how a pendulum swings in the air, how Earth revolves around the sun, and so on. Absolutely everything contained within the book’s first five chapters requires the use of the most basic building block for programming motion, the vector. And so that’s where I’ll begin the story.

The word vector can mean a lot of different things. It’s the name of a New Wave rock band formed in Sacramento, California, in the early 1980s, and the name of a breakfast cereal manufactured by Kellogg’s Canada. In the field of epidemiology, a vector is an organism that transmits infection from one host to another. In the C++ programming language, a vector (std::vector) is an implementation of a dynamically resizable array data structure.

While all these definitions are worth exploring, they’re not the focus here. Instead, this chapter dives into the Euclidean vector (named for the Greek mathematician Euclid), also known as the geometric vector. When you see the term vector in this book, you can assume it refers to a Euclidean vector, defined as an entity that has both magnitude and direction.

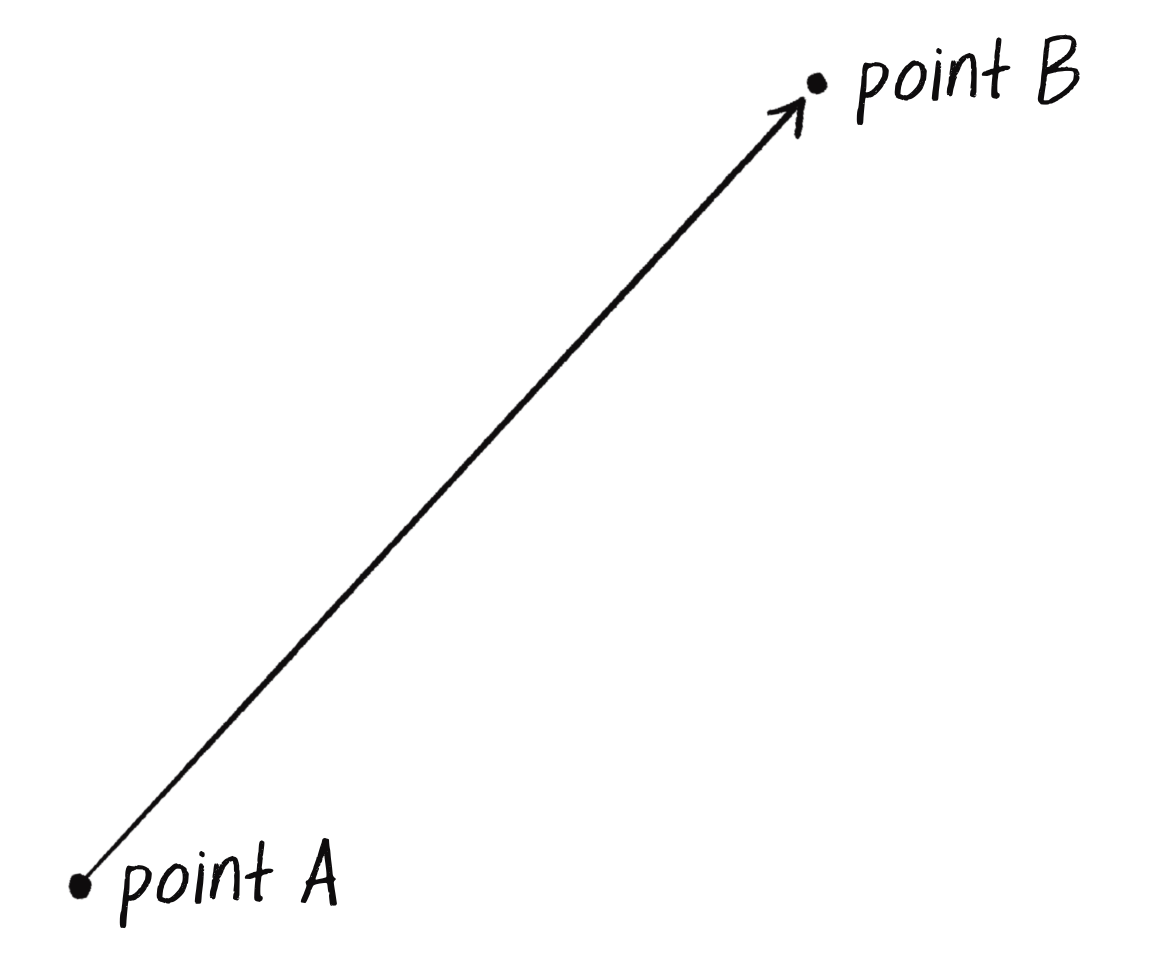

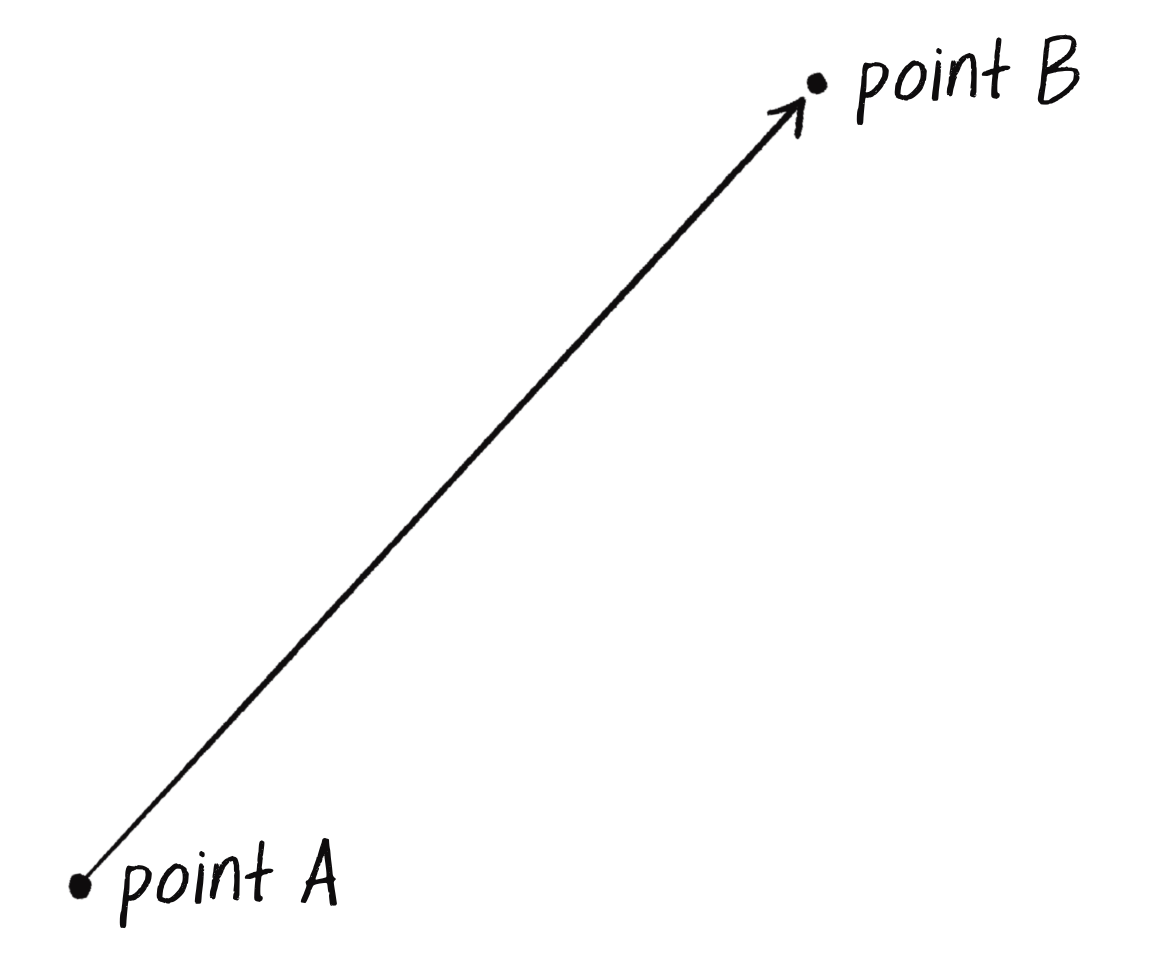

A vector is typically drawn as an arrow, as in Figure 1.1. The vector’s direction is indicated by where the arrow is pointing, and its magnitude by the length of the arrow itself.

The vector in Figure 1.1 is drawn as an arrow from point A to point B. It serves as an instruction for how to travel from A to B.

Before diving into more of the details about vectors, I’d like to create a p5.js example that demonstrates why you should care about vectors in the first place. If you’ve watched any beginner p5.js tutorials, read any introductory p5.js textbooks, or taken an introduction to creative coding course (and hopefully you’ve done one of these things to help prepare you for this book!), you probably, at one point or another, learned how to write a bouncing ball sketch.

// Variables for position and speed of ball.

let x = 100;

let y = 100;

let xspeed = 2.5;

let yspeed = 2;

function setup() {

createCanvas(640, 240);

background(255);

}

function draw() {

background(255);

// Move the ball according to its speed.

x = x + xspeed;

y = y + yspeed;

//{!6} Check for bouncing.

if (x > width || x < 0) {

xspeed = xspeed * -1;

}

if (y > height || y < 0) {

yspeed = yspeed * -1;

}

stroke(0);

fill(127);

//{!1} Draw the ball at the position (x,y).

circle(x, y, 48);

}

In this example, there’s a flat, two-dimensional world—a blank canvas—with a circular shape (a “ball”) traveling around. This ball has properties like position and speed that are represented in the code as variables.

| Property | Variable Names |

|---|---|

| position | x and y |

| speed | xspeed and yspeed |

In a more sophisticated sketch, you might have many more variables representing other properties of the ball and its environment:

| Property | Variable Names |

|---|---|

| acceleration | xacceleration and yacceleration |

| target position | xtarget and ytarget |

| wind | xwind and ywind |

| friction | xfriction and yfriction |

You might notice that for every concept in this world (wind, position, acceleration, and the like), there are two variables. And this is only a two-dimensional world. In a 3D world, you’d need three variables for each property: x, y, and z for position, xspeed, yspeed, and zspeed for speed, and so on. Wouldn’t it be nice to simplify the code to use fewer variables? Instead of starting the program with something like this:

let x; let y; let xspeed; let yspeed;

I’d love to start it with something like this:

let position; let speed;

Thinking of the ball’s properties as vectors instead of a loose collection of separate values will allow me to do just that.

Taking this first step toward using vectors won’t let you do anything new or magically turn a p5.js sketch into a full-on physics simulation. However, using vectors will help organize your code and provide a set of methods for common mathematical operations you’ll need over and over and over again while programming motion.

As an introduction to vectors, I’m going to stick to two dimensions for quite some time (at least the first several chapters). All of these examples can be fairly easily extended to three dimensions (and the class I’ll use, p5.Vector, allows for three dimensions). However, for the purposes of learning the fundamentals, the added complexity of the third dimension would be a distraction.

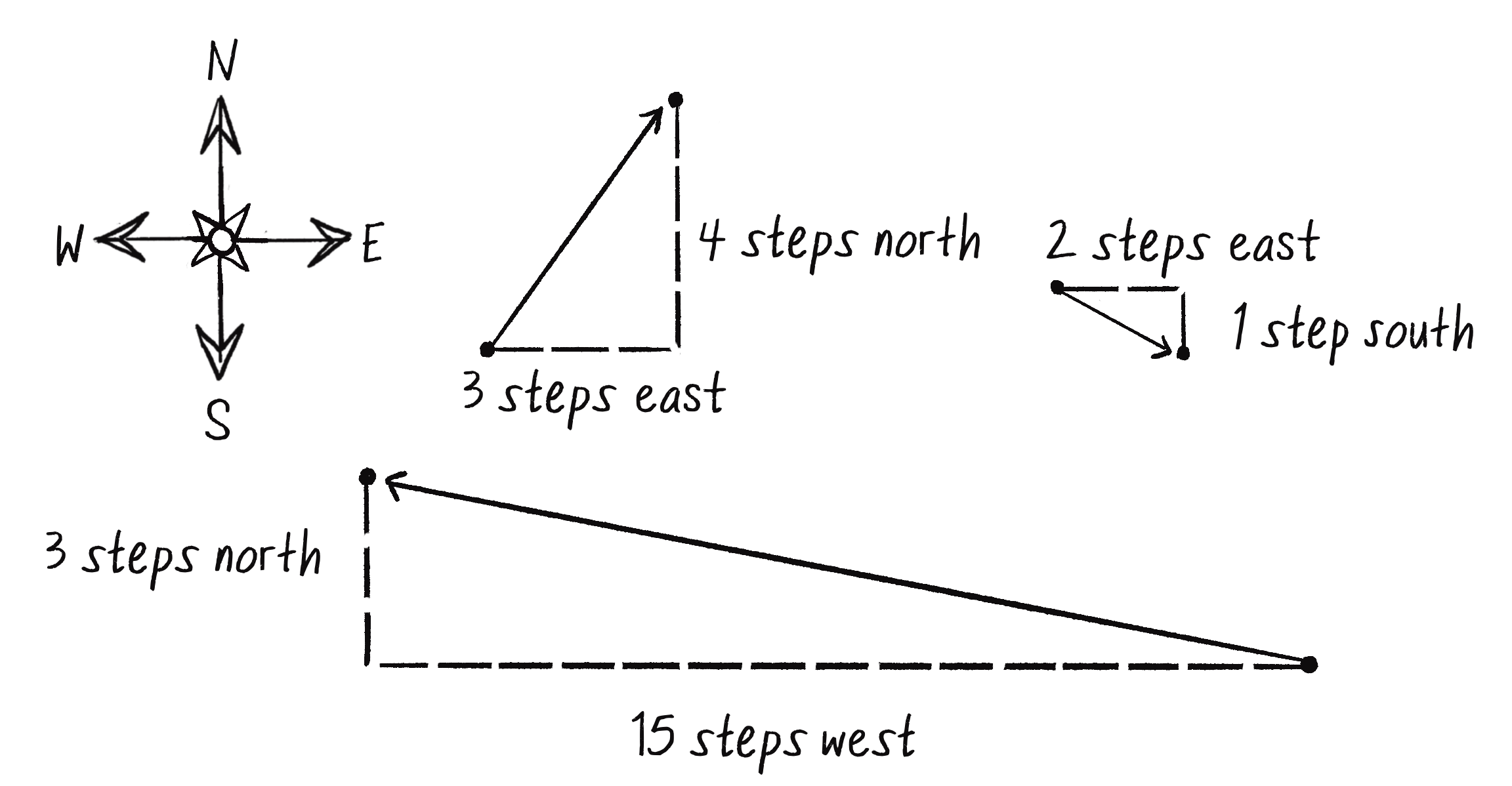

Think of a vector as the difference between two points, or as instructions for walking from one point to another. For example, Figure 1.2 shows some vectors and possible interpretations of them.

These vectors could be thought of in the following way:

| Vector | Instructions |

|---|---|

| (-15, 3) | Walk fifteen steps west; turn and walk three steps north. |

| (3, 4) | Walk three steps east; turn and walk four steps north. |

| (2, -1) | Walk two steps east; turn and walk one step south. |

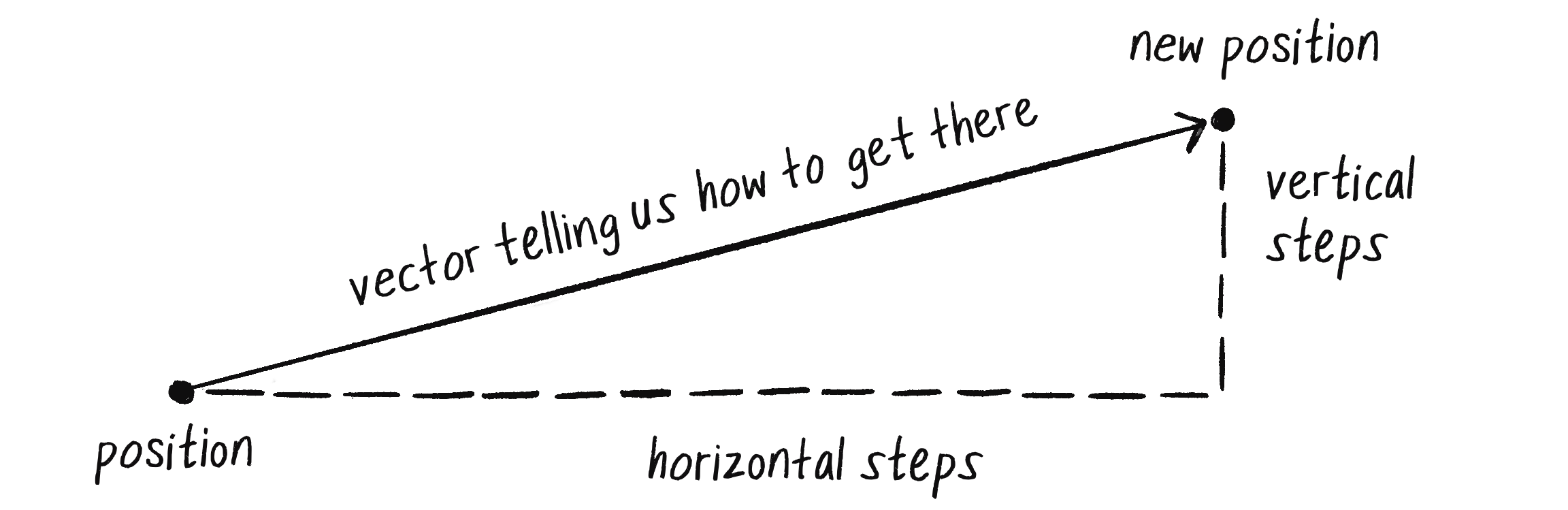

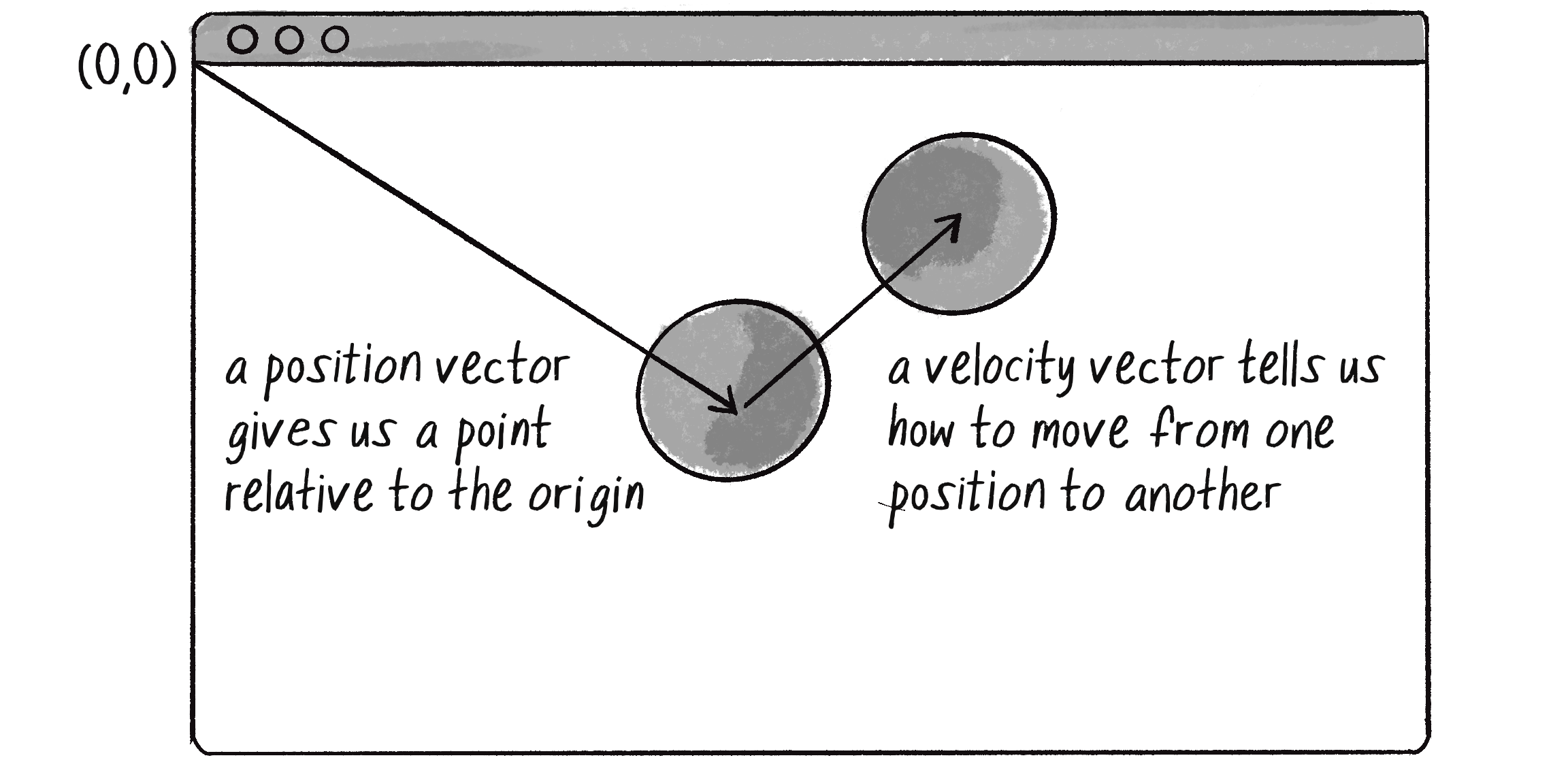

You’ve probably already thought this way when programming motion. For every frame of animation (a single cycle through p5’s draw() loop), you instruct each object to reposition itself to a new spot a certain number of pixels away horizontally and a certain number of pixels away vertically. This instruction is essentially a vector, as in Figure 1.3; it has both magnitude (how far away did you travel?) and direction (which way did you go).

The vector sets the object’s velocity, defined as the rate of change of the object’s position with respect to time. In other words, the velocity vector determines the object’s new position for every frame of the animation, according to this basic algorithm for motion: the new position is equal to the result of applying the velocity to the current position.

If velocity is a vector (the difference between two points), what about position? Is it a vector too? Technically, you could argue that position is not a vector, since it’s not describing how to move from one point to another—it’s describing a single point in space. Nevertheless, another way to describe a position is as the path taken from the origin—point (0,0)—to the current point. When you think of position in this way, it becomes a vector, just like velocity, as in Figure 1.4.

In Figure 1.4, the vectors are placed on a computer graphics canvas. Unlike in Figure 1.2, the origin point (0,0) isn’t the center, it’s the top-left corner. And instead of north, south, east, and west, there are positive and negative directions along the x- and y-axes (with y pointing down in the positive direction).

Let’s examine the underlying data for both position and velocity. In the bouncing ball example, I originally had the following variables:

| Property | Variable Names |

|---|---|

| position | x, y |

| velocity | xspeed, yspeed |

Now I’ll treat position and velocity as vectors instead, each represented by an object with x and y attributes. If I were to write a Vector class myself, I’d start with something like this:

class Vector {

constructor(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

}

Notice how this class is designed to store the same data as before—two floating-point numbers per vector, an x value and a y value. At its core, a Vector object is just a convenient way to store two values (or three, as you’ll see in 3D examples) under one name.

As it happens, p5.js already has a built-in p5.Vector class, so I don’t need to write one myself. And so this . . .

let x = 100; let y = 100; let xspeed = 1; let yspeed = 3.3;

becomes . . .

let position = createVector(100, 100); let velocity = createVector(1, 3.3);

Notice that the position and velocity vector objects aren’t created, as you might expect, by invoking a constructor function. Instead of writing new p5.Vector(x, y), I’ve called createVector(x, y). The createVector() function is included in p5.js as a helper function to take care of details behind the scenes upon creation of the vector. Except in special circumstances, you should always create p5.Vector objects with createVector(). I should note that p5.js functions such as createVector() can’t be executed outside of setup() or draw(), since the library won’t yet be loaded. I’ll demonstrate how to address this when I tackle the full bouncing ball example with vectors.

Now that there are two vector objects (position and velocity), I’m ready to implement the vector-based algorithm for motion: position = position + velocity. In Example 1.1, without vectors, the code reads:

// Add each speed to each position. x = x + xspeed; y = y + yspeed;

In an ideal world, I would be able to rewrite this as:

// Add the velocity vector to the position vector. position = position + velocity;

In JavaScript, however, the addition operator + is reserved for primitive values (integers, floats, and the like). JavaScript doesn’t know how to add two p5.Vector objects together any more than it knows how to add two p5.Font objects or p5.Image objects. Fortunately, the p5.Vector class includes methods for common mathematical operations.

Before I continue looking at the p5.Vector class and the add() method, let’s examine vector addition using the notation found in math and physics textbooks. Vectors are typically written either in boldface type or with an arrow on top. For the purposes of this book, to distinguish a vector (with magnitude and direction) from a scalar (a single value, such as an integer or a floating-point number), I’ll use the arrow notation:

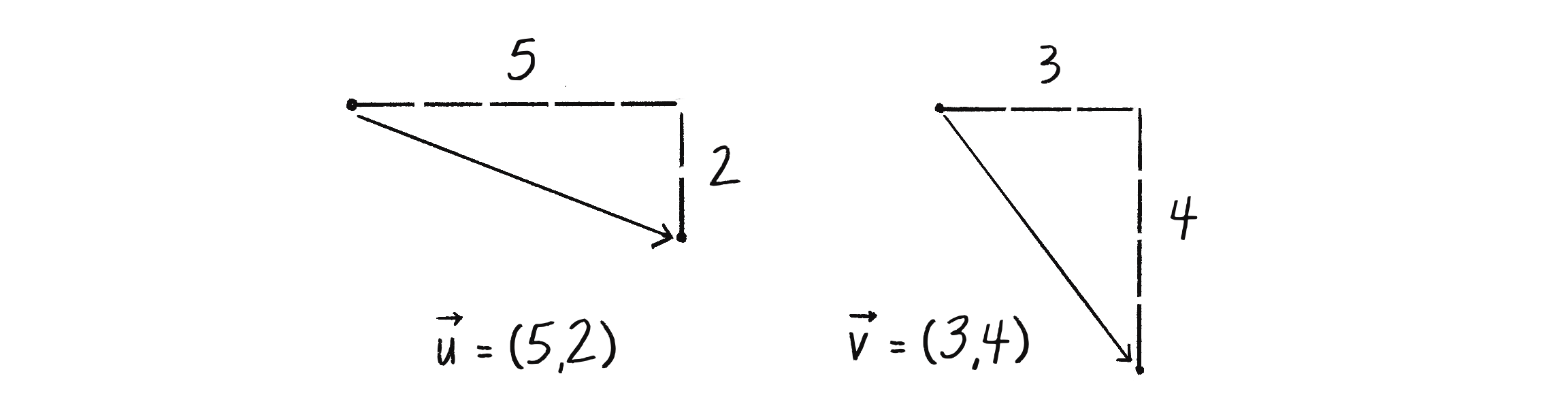

Let’s say I have the two vectors shown in Figure 1.5.

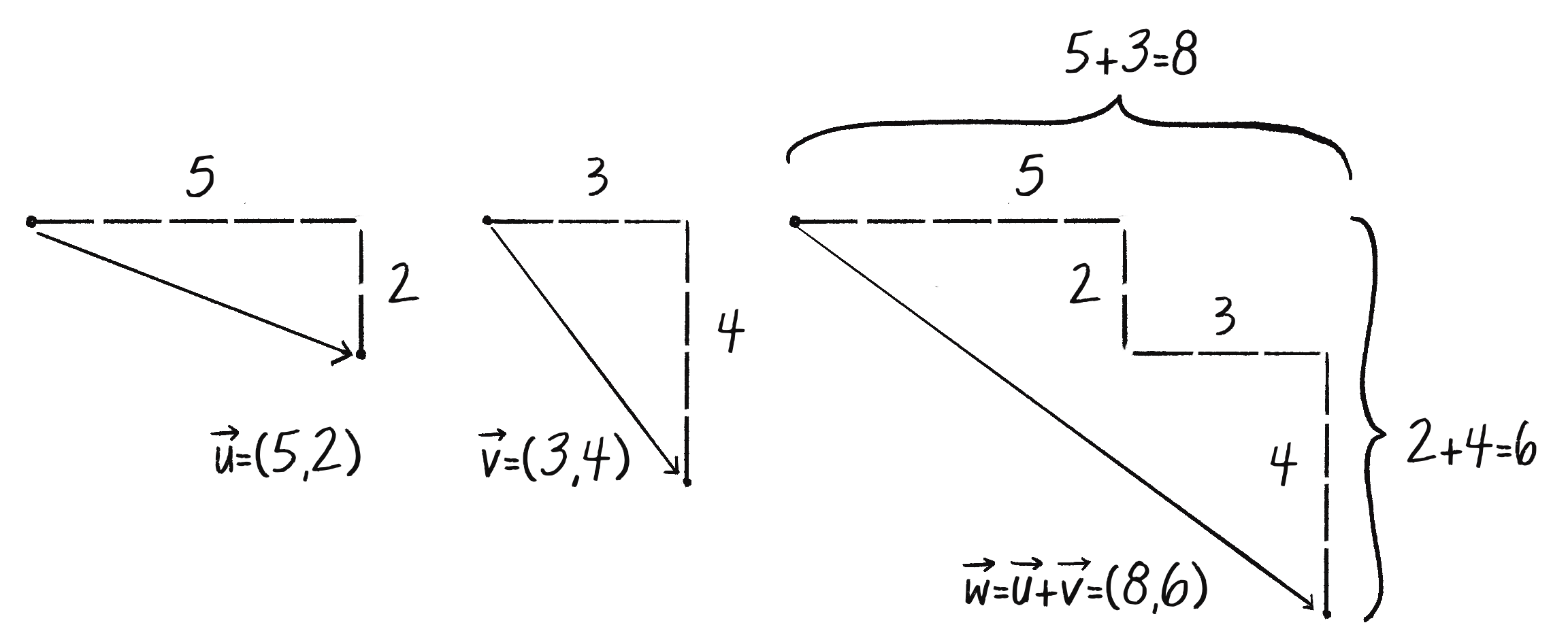

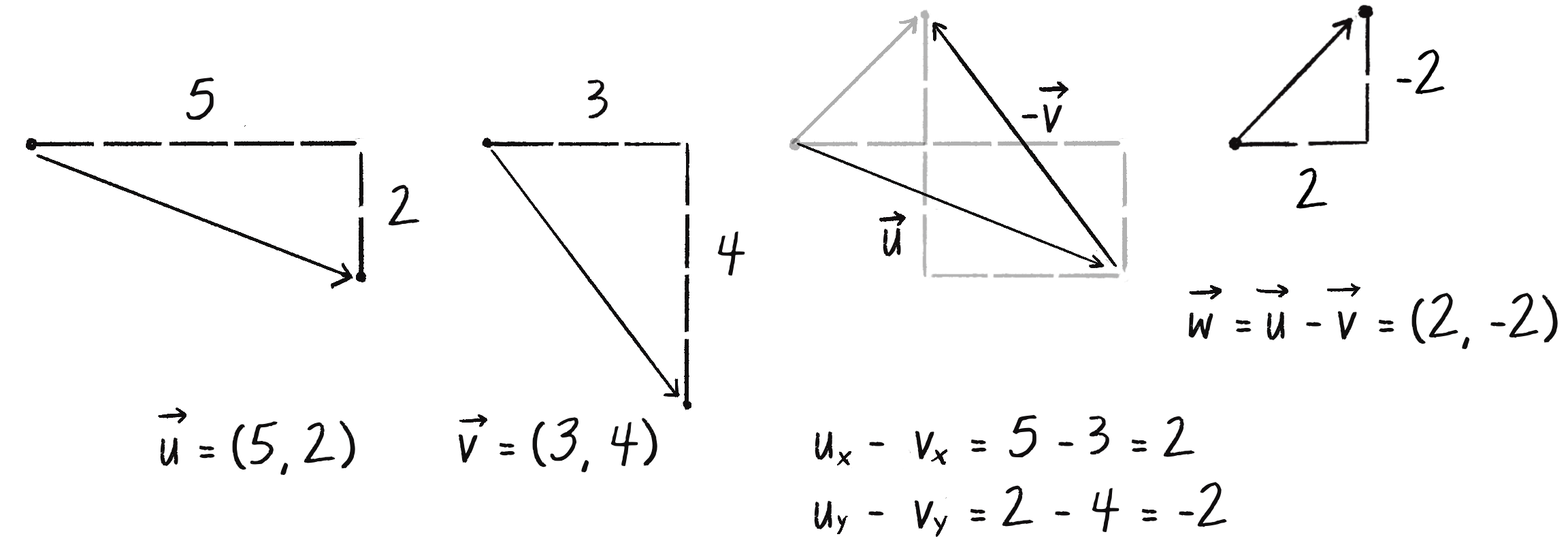

Each vector has two components, an x and a y. To add the two vectors together, add both x components and y components to create a new vector, as in Figure 1.6.

In other words, \vec{w} = \vec{u} + \vec{v} can be written as:

Then, replacing \vec{u} and \vec{v} with their values from Figure 1.6, you get:

Finally, write the result as a vector:

Addition with vectors follows the same algebraic rules as with real numbers.

The commutative rule: \vec{u} + \vec{v} = \vec{v} + \vec{u}

The associative rule: \vec{u} + (\vec{v} + \vec{w}) = (\vec{u} + \vec{v}) + \vec{w}

Fancy terminology and symbols aside, these rules boil down to quite a simple concept: the result is the same no matter the order in which the vectors are added. Replace the vectors with regular numbers (scalars) and these rules are easy to see:

Now that I’ve covered the theory behind adding two vectors together, I can turn to adding vector objects in p5.js. Imagine again that I’m creating my own Vector class. I could give it a function called add() that takes another Vector object as its argument:

class Vector {

constructor(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

//{!4 .bold} New! A function to add another Vector to this Vector. Add the x components and the y components separately.

add(v) {

this.x = this.x + v.x;

this.y = this.y + v.y;

}

}

The function looks up the x and y components of the two vectors and adds them separately. This is exactly how the built-in p5.Vector class’s add() function is written, too. Knowing how it works, I can now return to the bouncing ball example with its position + velocity algorithm and implement vector addition:

//{!1 .line-through} This does not work!

position = position + velocity;

//{!1} Add the velocity to the position.

position.add(velocity);

Now we have what we need to rewrite the bouncing ball example with vectors.

//{!2 .bold} Instead of a bunch of floats, we now just have two variables.

let position;

let velocity;

function setup() {

createCanvas(640, 240);

//{!2 .bold} Note how createVector() has to be called inside of setup().

position = createVector(100, 100);

velocity = createVector(2.5, 2);

}

function draw() {

background(255);

//{!1 .bold .no-comment}

position.add(velocity);

//{!6 .bold .code-wide} We still sometimes need to refer to the individual components of a p5.Vector and can do so using the dot syntax: position.x, velocity.y, etc.

if (position.x > width || position.x < 0) {

velocity.x = velocity.x * -1;

}

if (position.y > height || position.y < 0) {

velocity.y = velocity.y * -1;

}

stroke(0);

fill(127);

circle(position.x, position.y, 48);

}

At this stage, you might feel somewhat disappointed. After all, these changes may appear to have made the code more complicated than the original version. While this is a perfectly reasonable and valid critique, it’s important to understand that the power of programming with vectors hasn’t been fully realized just yet. Looking at a bouncing ball and only implementing vector addition is just the first step. As I move forward into a more complex world of multiple objects and multiple forces (which I’ll introduce in Chapter 2) acting on those objects, the benefits of vectors will become more apparent.

I should, however, note an important aspect of the transition to programming with vectors. Even though I’m using p5.Vector objects to encapsulate two values—the x and y of the ball’s position or the x and y of the ball’s velocity—under a single variable name, I’ll still often need to refer to the x and y components of each vector individually.

The circle() function doesn’t allow for a p5.Vector object as an argument. A circle can only be drawn with two scalar values, an x-coordinate and a y-coordinate. And so I must dig into the p5.Vector object and pull out the x and y components using object-oriented dot syntax:

//{!1} .line-through .no-comment}

circle(position, 48);

circle(position.x, position.y, 48);

The same issue arises when testing if the circle has reached the edge of the window. In this case, I need to access the individual components of both vectors, position and velocity:

if ((position.x > width) || (position.x < 0)) {

velocity.x = velocity.x * -1;

}

It may not always be obvious when to directly access an object's properties versus when to reference the object as a whole or use one of its methods. The goal of this chapter (and most of this book) is to help you distinguish between these scenarios by providing a variety of examples and use cases.

Take one of the walker examples from the Chapter 0 and convert it to use vectors.

Find something else you’ve previously made in p5.js using separate x and y variables, and use vectors instead.

Extend the bouncing ball with vectors example into 3D. Can you get a sphere to bounce around a box?

Addition was really just the first step. There are many mathematical operations commonly used with vectors. Here’s a comprehensive table of the operations available as methods in the p5.Vector class. Remember, these are not standalone functions, but rather methods associated with the p5.Vector class. When you see the word “this” in the table below, it refers to the specific vector the method is operating on.

| Method | Task |

|---|---|

add() |

Adds a vector to this vector |

sub() |

Subtracts a vector from this vector |

mult() |

Scale this vector with multiplication |

div() |

Scale this vector with division |

mag() |

Returns the magnitude of this vector |

setMag() |

Set the magnitude of this vector |

normalize() |

Normalize this vector to a unit length of 1 |

limit() |

Limit the magnitude of this vector |

heading() |

Returns 2D heading of this vector expressed as an angle |

rotate() |

Rotate this 2D vector by an angle |

lerp() |

Linear interpolate to another vector |

dist() |

The Euclidean distance between two vectors (considered as points) |

angleBetween() |

Find the angle between two vectors |

dot() |

Returns the dot product of two vectors |

cross() |

Returns the cross product of two vectors (only relevant in three dimensions) |

random2D() |

Returns a random 2D vector |

random3D() |

Returns a random 3D vector |

I’ll go through a few of the key methods now. As the examples get more sophisticated in later chapters, I’ll continue to reveal the details of more of them.

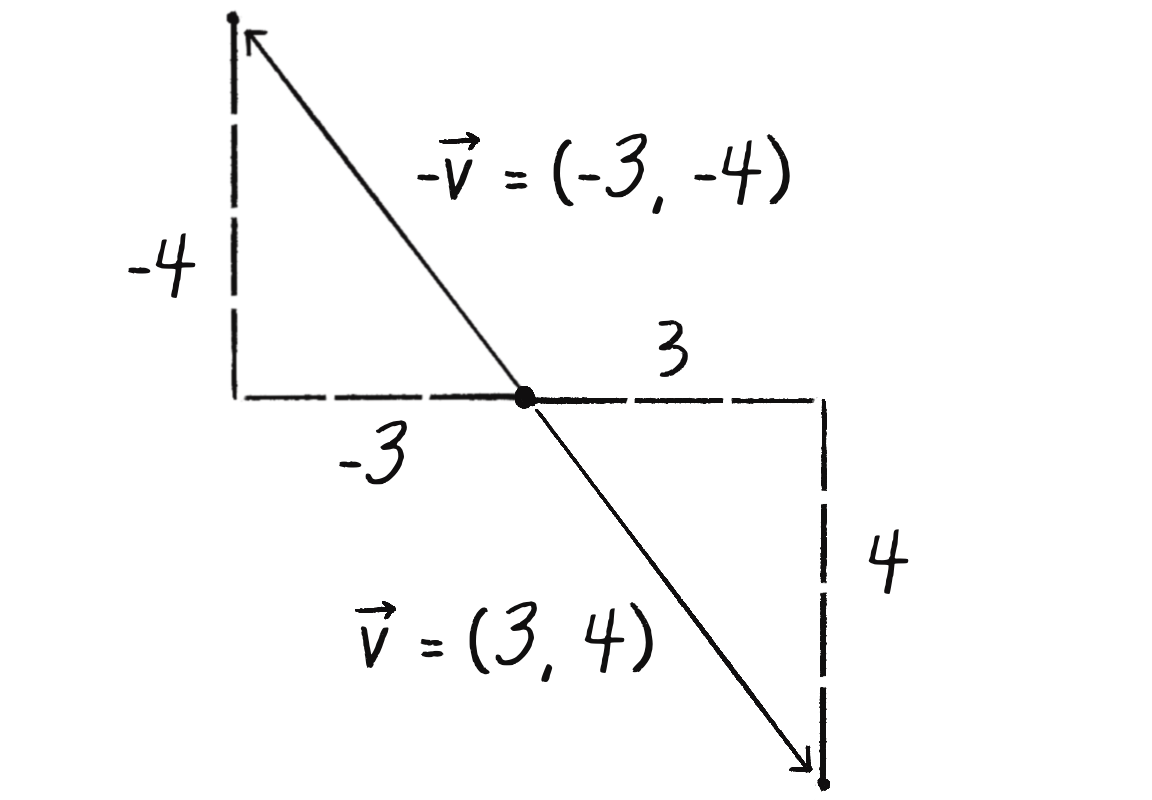

Having already covered addition, I’ll now turn to subtraction. This one’s not so bad; just take the plus sign and replace it with a minus! Before tackling subtraction itself, however, consider what it means for a vector \vec{v} to become -\vec{v}. The negative version of the scalar 3 is -3. A negative vector is similar: the polarity of each of the vector’s components is inverted. So if \vec{v} has the components (x, y), then -\vec{v} is (-x, -y). Visually, this results in an arrow of the same length as the original vector pointing in the opposite direction, as depicted in Figure 1.7.

Subtraction, then, is the same as addition, only with the second vector in the equation treated as a negative version of itself:

Just as vectors are added by placing them “tip to tail”—that is, aligning the tip (or end point) of one vector with the tail (or start point) of the next—vectors are subtracted by reversing the direction of the second vector and and placing it at the end of the first, as in Figure 1.8 .

To actually solve the subtraction, take the difference of the vectors’ components. That is, \vec{w} = \vec{u} - \vec{v} can be written as:

Inside p5.Vector, the code reads:

sub(v) {

this.x = this.x - v.x;

this.y = this.y - v.y;

}

The following example demonstrates vector subtraction by taking the difference between two points (that are treated as vectors): the mouse position and the center of the window.

function draw() {

background(255);

//{!2} Two vectors, one for the mouse location and one for the center of the window

let mouse = createVector(mouseX, mouseY);

let center = createVector(width / 2, height / 2);

//{!3} Draw the original two vectors

stroke(200);

strokeWeight(4);

line(0, 0, mouse.x, mouse.y);

line(0, 0, center.x, center.y);

// Vector subtraction!

mouse.sub(center);

//{!3} Draw a line to represent the result of subtraction.

// Notice how I move the origin with translate() to place the vector

stroke(0);

translate(width / 2, height / 2);

line(0, 0, mouse.x, mouse.y);

}

Note the use of translate() to visualize the resulting vector as a line from the center (width/2, height/2) to the mouse. Vector subtraction is its own kind of translation, moving the “origin” of a position vector. Here, by subtracting the center vector from the mouse vector, I’m effectively “moving” the starting point of resulting vector to the center of the canvas. Therefore I also need to move the origin using translate(). Without this, the line would be drawn from the top-left corner, and the visual connection wouldn’t be as clear.

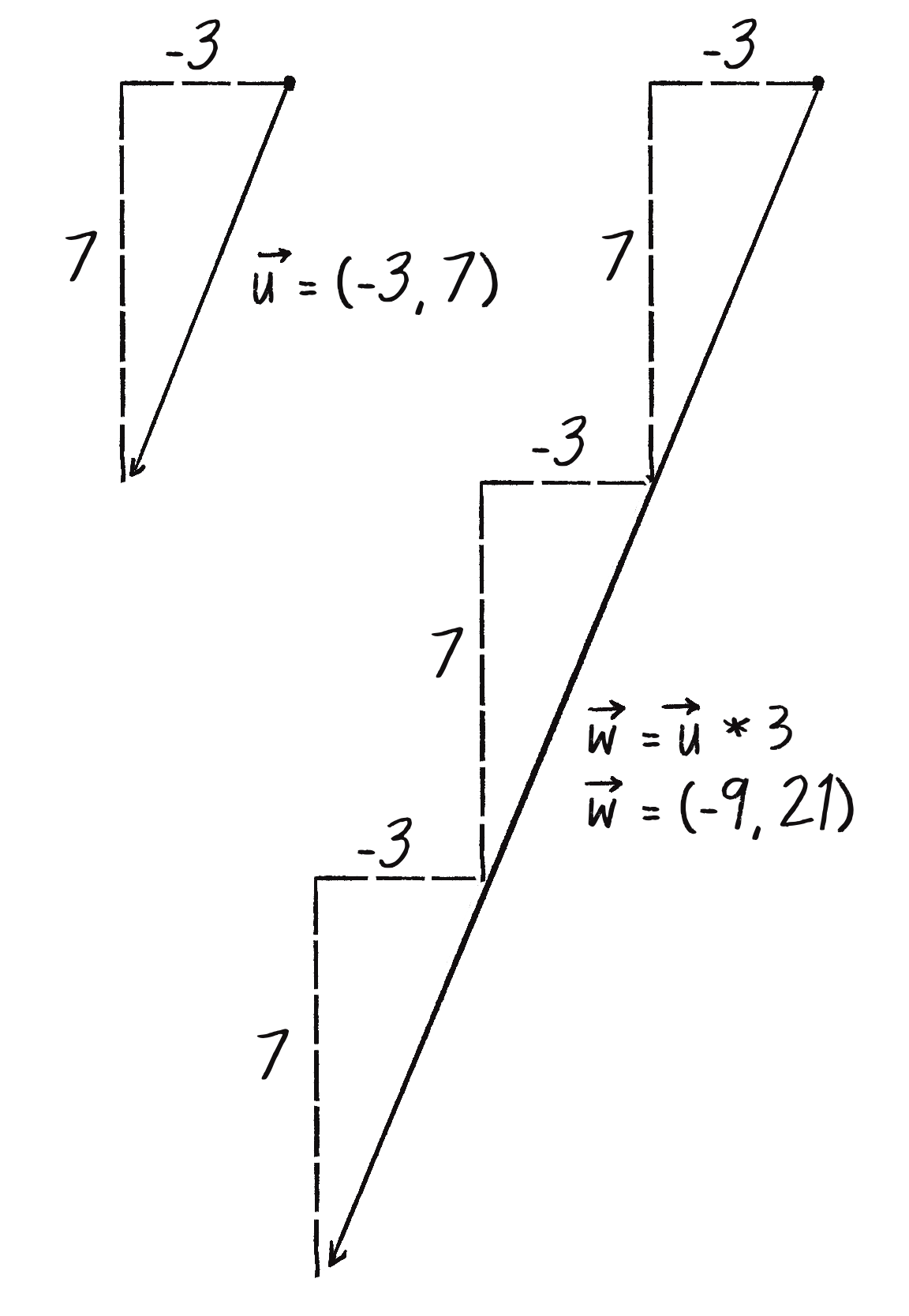

Moving on to multiplication, you have to think a bit differently. Multiplying a vector typically refers to the process of scaling a vector. If I want to scale a vector to twice its size or one-third of its size, while leaving its direction the same, I would say: “Multiply the vector by 2” or “Multiply the vector by 1/3.” Unlike with addition and subtraction, I’m multiplying the vector by a scalar (a single number), not by another vector. Figure 1.9 illustrates how to scale a vector by a factor of 3.

To scale a vector, multiply each component (x and y) by a scalar. That is, \vec{w} = \vec{u} * n can be written as:

As an example, say \vec{u} = (-3, 7) and n = 3. You can calculate \vec{w} = \vec{u} * nas follows:

This is exactly how the mult() function inside the p5.Vector class works.

mult(n) {

//{!2} The components of the vector are multiplied by a number.

this.x = this.x * n;

this.y = this.y * n;

}

Implementing multiplication in code is as simple as:

let u = createVector(-3, 7); // This p5.Vector is now three times the size and is equal to (-9, 21). (See Figure 1.9) u.mult(3);

Example 1.4 illustrates vector multiplication by drawing a line between the mouse and the center of the canvas, as in the previous example, and then scaling that line by 0.5.

function draw() {

background(255);

let mouse = createVector(mouseX, mouseY);

let center = createVector(width / 2, height / 2);

mouse.sub(center);

translate(width / 2, height / 2);

strokeWeight(2);

stroke(200);

line(0, 0, mouse.x, mouse.y);

//{!1} Multiplying a vector! The vector is now half its original size (multiplied by 0.5).

mouse.mult(0.5);

stroke(0);

strokeWeight(4);

line(0, 0, mouse.x, mouse.y);

}

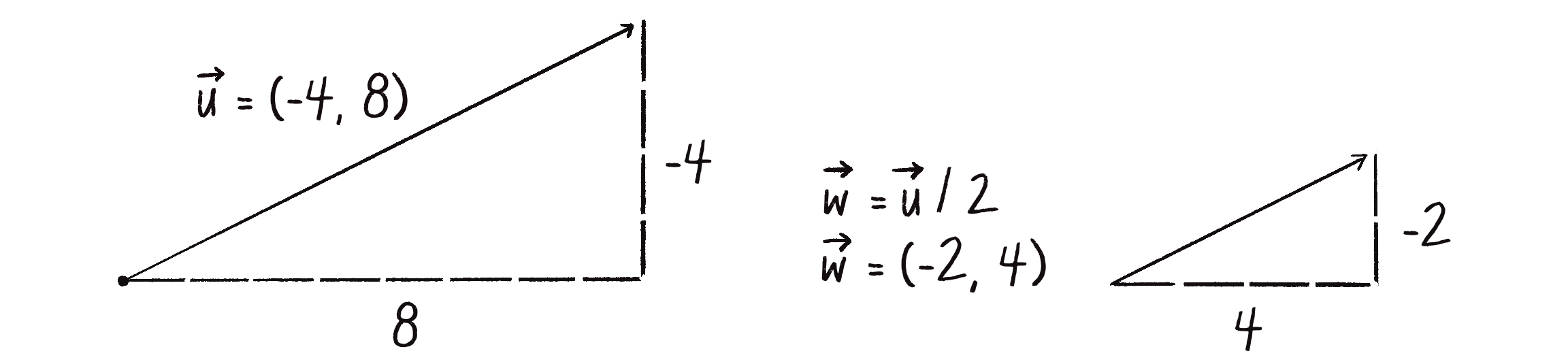

The resulting vector is half its original size. Rather than multiplying the vector by 0.5, I could also achieve the same effect by dividing the vector by 2, as in Figure 1.10.

Vector division, then, works just like vector multiplication—just replace the multiplication sign (*) with the division sign (/). Here’s how the p5.Vector class implements the div() function:

div(n) {

this.x = this.x / n;

this.y = this.y / n;

}

And here’s how to use the div() function in a sketch:

let u = createVector(8, -4); // Dividing a vector! The vector is now half its original size (divided by 2). u.div(2);

This takes the vector u and divides it by 2.

As with addition, basic algebraic rules of multiplication apply to vectors.

The associative rule: (n * m) * \vec{v} = n * (m * \vec{v})

The distributive rule with two scalars, one vector: (n + m) * \vec{v} = (n * \vec{v}) + (m * \vec{v})

The distributive rule with two vectors, one scalar: (\vec{u} + \vec{v}) * n = (\vec{u} * n) + (\vec{v} * n)

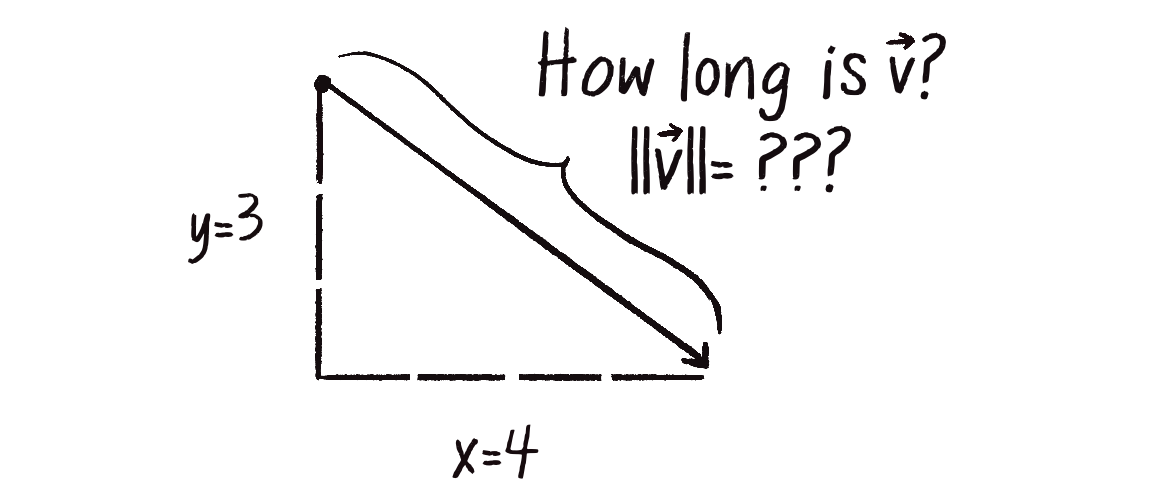

Multiplication and division, as just described, alter the length of a vector without affecting its direction. Perhaps you’re wondering: “OK, so how do I know what the length of a vector is? I know the vector’s components (x and y), but how long (in pixels) is the actual arrow?” Understanding how to calculate the length of a vector, also known as its magnitude, is incredibly useful and important.

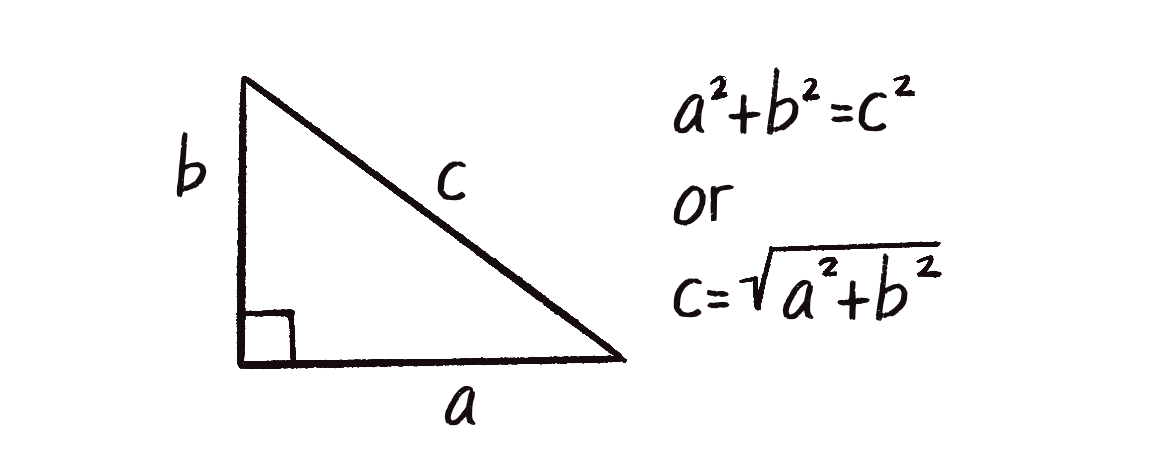

Notice in Figure 1.11 how the vector, drawn as an arrow and two components (x and y), creates a right triangle. The sides are the components, and the hypotenuse is the arrow itself. We’re lucky to have this right triangle, because once upon a time, a Greek mathematician named Pythagoras discovered a lovely formula that describes the relationship between the sides and hypotenuse of a right triangle. This formula, the Pythagorean theorem, is a^2 + b^2 = c^2, or a squared plus b squared equals c squared (see Figure 1.12).

Armed with this formula, we can now compute the magnitude of \vec{v} as follows:

In the p5.Vector class, the mag() function is defined using the same formula:

mag() {

return sqrt(this.x * this.x + this.y * this.y);

}

Here’s a sketch that calculates the magnitude of the vector between the mouse and the center of the canvas, and visualizes it as a rectangle drawn across the top of the window.

function setup() {

createCanvas(640, 240);

}

function draw() {

background(255);

let mouse = createVector(mouseX, mouseY);

let center = createVector(width / 2, height / 2);

mouse.sub(center);

//{!3} The magnitude (i.e. length) of a vector can be accessed via the mag() function. Here it is used as the width of a rectangle drawn at the top of the window.

let m = mouse.mag();

fill(0);

rect(0, 0, m, 10);

translate(width / 2, height / 2);

line(0, 0, mouse.x, mouse.y);

}

Notice how the magnitude (length) of a vector is always positive, even if the vector’s components are negative.

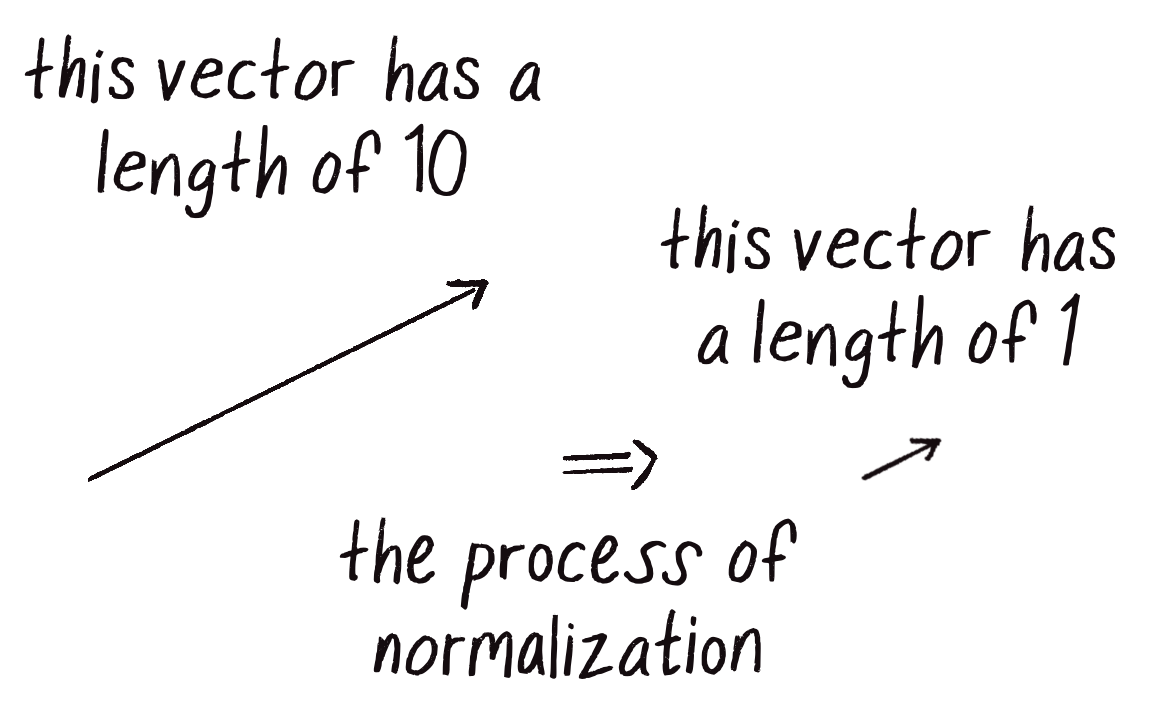

Calculating the magnitude of a vector is only the beginning. It opens the door to many possibilities, the first of which is normalization (Figure 1.13). This is the process of making something “standard” or, well . . . “normal.” In the case of vectors, the convention is that a standard vector has a length of 1. To normalize a vector, therefore, is to take a vector of any length and change its length to 1, without changing its direction. That normalized vector is then called a unit vector.

A unit vector describes a vector’s direction without regard to its length. You’ll see this come in especially handy once I start to work with forces in Chapter 2.

For any given vector \vec{u} , its unit vector (written as \hat{u}) is calculated as follows:

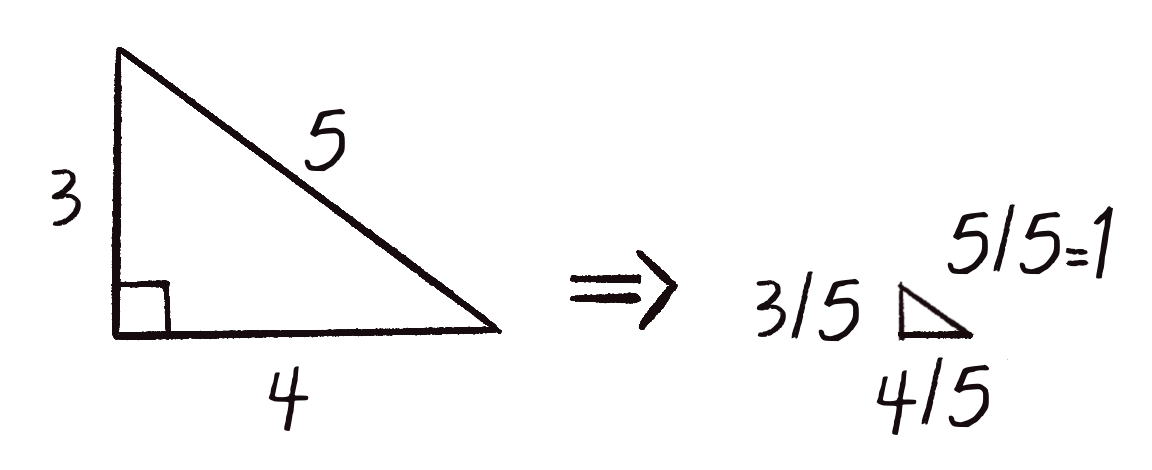

In other words, to normalize a vector, divide each component by the vector’s magnitude. To see why this works, consider a vector (4,3), which has a magnitude of 5 (see Figure 1.14). Once normalized, the vector will have a magnitude of 1. Thinking of the vector as a right triangle, normalization shrinks the hypotenuse down by dividing by 5 (since 5/5 = 1). In that process, each sides shrinks as well, also by a factor of 5. The side lengths go from 4 and 3 to 4/5 and 3/5.

In the p5.Vector class, the normalization method is written as follows:

normalize() {

let m = this.mag();

this.div(m);

}

Of course, there’s one small issue. What if the magnitude of the vector is 0? You can’t divide by 0! Some quick error checking fixes that right up:

normalize() {

let m = this.mag();

if (m > 0) {

this.div(m);

}

}

This sketch uses normalization to give the vector between the mouse and the center of the canvas a fixed length, regardless of the actual magnitude of the original vector.

function draw() {

background(255);

let mouse = createVector(mouseX, mouseY);

let center = createVector(width / 2, height / 2);

mouse.sub(center);

translate(width / 2, height / 2);

stroke(200);

strokeWeight(2);

line(0, 0, mouse.x, mouse.y);

//{!2} In this example, after the vector is normalized, it is multiplied by 50. Note that no matter where the mouse is, the vector always has the same length (50) due to the normalization process.

mouse.normalize();

mouse.mult(50);

stroke(0);

strokeWeight(8);

line(0, 0, mouse.x, mouse.y);

}

Notice how I’ve multiplied the mouse vector by 50 after normalizing it to 1. Normalization is often the first step in creating a vector of a specific length, even if the desired length is something other than 1. You’ll see more of this later in the chapter.

All this vector math stuff sounds like something you should know about, but why? How will it actually help you write code? Patience. It’ll take some time before the awesomeness of using p5.Vector fully comes to light. This is a fairly common occurrence when learning a new data structure. For example, when you first learn about arrays, it might seem like more work to use an array than to have several variables stand for multiple things. That plan quickly breaks down when you need 100, 1,000, or 10,000 things, however.

The same can be true for vectors. What might seem like more work now will pay off later, and pay off quite nicely. And you don’t have to wait too long, as your reward will come in the next chapter. For now, however, I’ll focus on how it works, and on how working with vectors provides a different way to think about motion.

What does it mean to program motion using vectors? You’ve gotten a taste of it in Example 1.2, the bouncing ball. The circle on screen has a position (where it is at any given moment) as well as a velocity (instructions for how it should move from one moment to the next). Velocity is added to position:

position.add(velocity);

Then the object is drawn at the new position:

circle(position.x, position.y, 48);

Together, these steps are Motion 101.

In the bouncing ball example, all of this code happened within setup() and draw(). What I want to do now is move toward encapsulating all of the logic for an object’s motion inside of a class. This way, I can create a foundation for programming moving objects that I can easily reuse again and again. (See "The Random Walker Class" in Chapter 0 for a brief review of the basics of object-oriented-programming .)

To start, I’m going to create a generic Mover class that will describe a shape moving around the canvas. For that, I must consider the following two questions:

The “Motion 101” algorithm answers both of these questions. First, a Mover object has two pieces of data, position and velocity, which are both p5.Vector objects. These are initialized in the object’s constructor. In this case, I’ll arbitrarily decide to initialize the Mover object by giving it a random position and velocity. Note the use of this with all variables that are part of the Mover object.

class Mover {

constructor() {

this.position = createVector(random(width), random(height));

this.velocity = createVector(random(-2,2), random(-2, 2));

}

The functionality follows suit. The Mover needs to move (by applying its velocity to its position) and it needs to be visible. I’ll implement these needs as functions named update() and show(). I’ll put all of the motion logic code in update() and draw the object in show().

update() {

//{!1} The Mover moves.

this.position.add(this.velocity);

}

show() {

stroke(0);

fill(175);

//{!1} The Mover is drawn as a circle.

circle(this.position.x, this.position.y, 48);

}

}

The Mover class also needs a function that determines what the object should do when it reaches the edge of the canvas. For now, I’ll do something simple, and have it wrap around the edges.

checkEdges() {

//{!11} When it reaches one edge, set position to the other.

if (this.position.x > width) {

this.position.x = 0;

} else if (this.position.x < 0) {

this.position.x = width;

}

if (this.position.y > height) {

this.position.y = 0;

} else if (this.position.y < 0) {

this.position.y = height;

}

}

Now the Mover class is finished, but the class itself isn’t an object; it’s a template for creating an instance of an object. To actually create a Mover object, I first need to declare a variable to hold it:

let mover;

Then, inside the setup() function, I create the object by invoking the class name along with the new keyword. This triggers the class’s constructor to make an instance of the object.

mover = new Mover();

Now all that remains is to call the appropriate functions in draw():

mover.update(); mover.checkEdges(); mover.show();

Here’s the entire example for reference:

//{!1} Declare Mover object.

let mover;

function setup() {

createCanvas(640, 240);

//{!1} Create Mover object.

mover = new Mover();

}

function draw() {

background(255);

//{!3} Call functions on Mover object.

mover.update();

mover.checkEdges();

mover.show();

}

class Mover {

constructor() {

//{!2} The object has two vectors: position and velocity.

this.position = createVector(random(width), random(height));

this.velocity = createVector(random(-2, 2), random(-2, 2));

}

update() {

//{!1} Motion 101: position changes by velocity.

this.position.add(this.velocity);

}

show() {

stroke(0);

strokeWeight(2);

fill(127);

circle(this.position.x, this.position.y, 48);

}

checkEdges() {

if (this.position.x > width) {

this.position.x = 0;

} else if (this.position.x < 0) {

this.position.x = width;

}

if (this.position.y > height) {

this.position.y = 0;

} else if (this.position.y < 0) {

this.position.y = height;

}

}

}

If object-oriented programming is at all new to you, one aspect here may seem a bit strange. I spent the beginning of this chapter discussing the p5.Vector class, and this class is the template for making the position object and the velocity object. So what are those objects doing inside of yet another object, the Mover object?

In fact, this is just about the most normal thing ever. An object is something that holds data (and functionality). That data can be numbers, or it can be other objects (arrays too)! You’ll see this over and over again in this book. In Chapter 4 , for example, I’ll write a class to describe a system of particles. That ParticleSystem object will include a list of Particle objects . . . and each Particle object will have as its data several p5.Vector objects!

You may have also noticed in the Mover class that I am setting the initial position and velocity directly within the constructor, without using any arguments. While this approach keeps things simple for now, in Chapter 2, I will explore the benefits of adding arguments to the constructor.

At this point, you hopefully feel comfortable with two things: (1) what a vector is, and (2) how to use vectors inside of an object to keep track of its position and movement. This is an excellent first step and deserves a mild round of applause. Before standing ovations are in order, however, you need to make one more, somewhat bigger step forward. After all, watching the Motion 101 example is fairly boring. The circle never speeds up, never slows down, and never turns. For more sophisticated motion—the kind of motion that appears in the world around us—one more vector needs to be added to the class: acceleration.

Acceleration is the rate of change of velocity. Think about that definition for a moment. Is it a new concept? Not really. Earlier I defined velocity as the rate of change of position, so in essence I’m developing a “trickle-down” effect. Acceleration affects velocity, which in turn affects position. (To provide some brief foreshadowing, this point will become even more crucial in the next chapter, when I look at how forces like friction affect acceleration, which affects velocity, which affects position.) In code, this trickle-down effect reads:

velocity.add(acceleration); position.add(velocity);

As an exercise, from this point forward, I’m going to make a rule for myself: I’ll try to write every example in the rest of this book without ever touching the values of velocity and position (except to initialize them). In other words, the goal for programming motion is to come up with an algorithm for how to calculate acceleration, and then let the trickle-down effect work its magic. (In truth, there will be a multitude of reasons to break this rule, and break it I shall. Nevertheless, it’s a useful constraint to begin with to illustrate the principles behind the motion algorithm with acceleration.)

The next step, then, is to come up with a way to calculate acceleration. Here are a few possible algorithms:

I’ll use the rest of this chapter to show you how to implement these algorithms.

Acceleration Algorithm #1, a constant acceleration, isn’t particularly interesting, but it’s the simplest and thus an excellent starting point to incorporate acceleration into the code. The first thing to do is add another variable to the Mover class:

class Mover {

constructor(){

//{!2} Initialize stationary mover at center of canvas

this.position = createVector(width / 2, height / 2);

this.velocity = createVector(0, 0);

//{!1 .bold} A new vector for acceleration

this.acceleration = createVector(0, 0);

}

Next, incorporate acceleration into the update() function:

update() {

//{!2 .bold} The motion algorithm is now two lines of code!

this.velocity.add(this.acceleration);

this.position.add(this.velocity);

}

I'm almost finished. The only missing piece is to get that mover moving! In the constructor, the initial velocity is set to zero, rather than a random vector as previously done. Therefore, when the sketch starts, the object is at rest. To get it moving instead of changing the velocity directly, I'll update it through the object's acceleration. According to Algorithm #1, the acceleration should be constant, so I'll choose a value now.

this.acceleration = createVector(-0.001, 0.01);

This means that for every frame of the animation, the object’s velocity should increase by -0.001 pixels in the x direction and 0.01 pixels in the y direction. Maybe you’re thinking, “Gosh, those values seem awfully small!” Indeed, they are quite tiny. but that’s by design. Acceleration values accumulate over time in the velocity, about 30 times per second depending on the sketch’s frame rate. To keep the magnitude of the velocity vector from growing too quickly and spiraling out of control, the acceleration values should remain quite small.

I can also help keep the velocity within a reasonable range by incorporating the p5.Vector function limit(), which puts a cap on the magnitude of a vector.

// The limit() function constrains the magnitude of a vector. this.velocity.limit(10);

This translates to the following:

What is the magnitude of velocity? If it’s less than 10, no worries; just leave it as is. If it’s more than 10, however, reduce it to 10!

Write the limit() function for the p5.Vector class.

limit(max) {

if (this.mag() > mag) {

this.normalize();

this.mult(max);

}

}

Let’s take a look at the changes to the Mover class, complete with acceleration and limit().

class Mover {

constructor() {

this.position = createVector(width / 2, height / 2);

this.velocity = createVector(0, 0);

// Acceleration is the key!

this.acceleration = createVector(-0.001, 0.01);

//{!1} The variable topspeed will limit the magnitude of velocity.

this.topSpeed = 10;

}

update() {

//{!2} Velocity changes by acceleration and is limited by topspeed.

this.velocity.add(this.acceleration);

this.velocity.limit(this.topSpeed);

this.position.add(this.velocity);

}

// show() is the same.

show() {}

//{!1} checkEdges() is the same.

checkEdges() {}

}

The net result is that the object falls down and to the left, gradually getting faster and faster until it reaches the maximum velocity.

Create a simulation of an object (think about a vehicle?) that accelerates when you press the up key and brakes when you press the down key.

Now on to Acceleration Algorithm #2, a random acceleration. In this case, instead of initializing acceleration in the object’s constructor, I want to randomly set its value inside the update() function. This way the object will get a different acceleration vector for every frame of the animation.

update() {

//{!1} The random2D() function returns a unit vector pointing in a random direction.

this.acceleration = p5.Vector.random2D();

this.velocity.add(this.acceleration);

this.velocity.limit(this.topspeed);

this.position.add(this.velocity);

}

The random2D() function produces a normalized vector, meaning it has a random direction, but its magnitude is always 1. To make things interesting, I can try scaling the random vector by a constant value:

this.acceleration = p5.Vector.random2D();

//{.bold} Constant

this.acceleration.mult(0.5);

Or, for even greater variety, I can scale the acceleration to a random value:

this.acceleration = p5.Vector.random2D();

//{.bold} Random

this.acceleration.mult(random(2));

This way the acceleration vector will have a random direction and a random magnitude between 0 and 2.

It’s crucial to understand that acceleration doesn’t merely refer to speeding up or slowing down. Rather, as this example has shown, it refers to any change in velocity—magnitude or direction. Acceleration is used to steer an object, and you’ll see this again and again in future chapters as I begin to code objects that make decisions about how to move.

You might also notice how this example is another kind of “random walker.” [CROSS REFERENCE]. A key distinction between what I’m doing here and the previous chapter’s examples, however, lies in what is being randomized. With the traditional random walker, I was directly manipulating the velocity, meaning each step was completely independent of the last. In this example, it’s the acceleration (the rate of change of velocity) that's being randomized, not the velocity itself. This makes the object's motion dependent on its previous state: the velocity changes incrementally according to the random acceleration. The resulting movement of the object has a kind of continuity and fluidity that the original random walker lacked. It may seem subtle, but it fundamentally changes the way the object moves about the canvas.

Referring back to the Chapter 0, implement an acceleration calculated with Perlin noise.

You might have noticed something a bit odd and unfamiliar in the previous example. The random2D() method used to create a random unit vector was called on the class name itself, as in p5.Vector.random2D(), rather than on the current instance of the class, as in this.random2D(). This is because random2D() is a static method, meaning it’s associated with the class as a whole rather than the individual objects themselves (that is, the instances of that class).

Static methods are rarely needed when you’re writing your own classes (like Walker or Mover), so you may not have encountered them before. They sometimes form an important part of prewritten classes like p5.Vector, however. In fact, Acceleration Algorithm #3 (accelerate toward the mouse), requires further use of this concept, so let’s take a step back and consider the difference between static and non-static methods.

Setting aside vectors for a second, take a look at the following code:

let x = 0; let y = 5; x = x + y;

This is probably what you’re used to, yes? x has a value of 0, add y to it, and now x is equal to 5. I could write similar code for adding two vectors:

let v = createVector(0, 0); let u = createVector(4, 5); v.add(u);

The vector v has the value of (0,0), I add the vector u to it, and now v is equal to (4,5). Makes sense, right?

Now consider this other example:

let x = 0; let y = 5; let z = x + y;

x has a value of 0, I add y to it, and store the result in a new variable z. The value of x doesn’t change here (neither does y)! This may seem like a trivial point, and one that is quite intuitive when it comes to mathematical operations with simple numbers. However, it’s not so obvious with mathematical operations using p5.Vector objects. Let’s try to rewrite the example with vectors, based on what I’ve covered of the p5.Vector class so far.

let v = createVector(0, 0); let u = createVector(4, 5); // Don’t be fooled; this is incorrect!!! let w = v.add(u);

This might seem like a good guess, but it’s just not the way the p5.Vector class works. If you look at the definition of add(), you can see why.

add(v) {

this.x = this.x + v.x;

this.y = this.y + v.y;

}

There are two problems here. First, the add() function doesn’t return a new p5.Vector object, and second, it changes the value of the vector upon which it’s called. In order to add two vector objects together and return the result as a new vector, I must use the static version of the add() function by calling it on the class name itself, rather than calling the non-static version on a specific object instance.

Here’s how I might write the static version of add() if I were declaring the class myself:

//{!1} The static version adds two vectors together and assigns the result to a new vector while leaving the original vectors (v and u above) intact.

static add(v1, v2) {

let v3 = createVector(v1.x + v2.x, v1.y + v2.y);

return v3;

}

The key difference here is that the function returns a new vector (v3) created using the sum of the components of v1 and v2. As a result, the function doesn’t make changes to either original vector.

When calling a static function, instead of referencing an object instance, you reference the name of the class itself. Here’s the right way to implement the vector addition example:

let v = createVector(0, 0);

let u = createVector(4, 5);

//{.line-through .no-comment}

let w = v.add(u);

//{.bold .no-comment}

let w = p5.Vector.add(v, u);

The p5.Vector class has static versions of add(), sub(), mult(), and div(). These static functions allow you to perform generic mathematical operations on vectors without changing the value of one of the input vectors in the process.

Translate the following pseudocode to code using static or non-static functions where appropriate.

v equals (1,5).u equals v multiplied by 2.w equals v minus u.let v = createVector(1, 5); let u = p5.Vector.mult(v, 2); let w = p5.Vector.sub(v, u); w.div(3);

To finish out this chapter, let’s try something a bit more complex and a great deal more useful. I’ll dynamically calculate an object’s acceleration according to the rule stated in Acceleration Algorithm #3: the object accelerates toward the mouse.

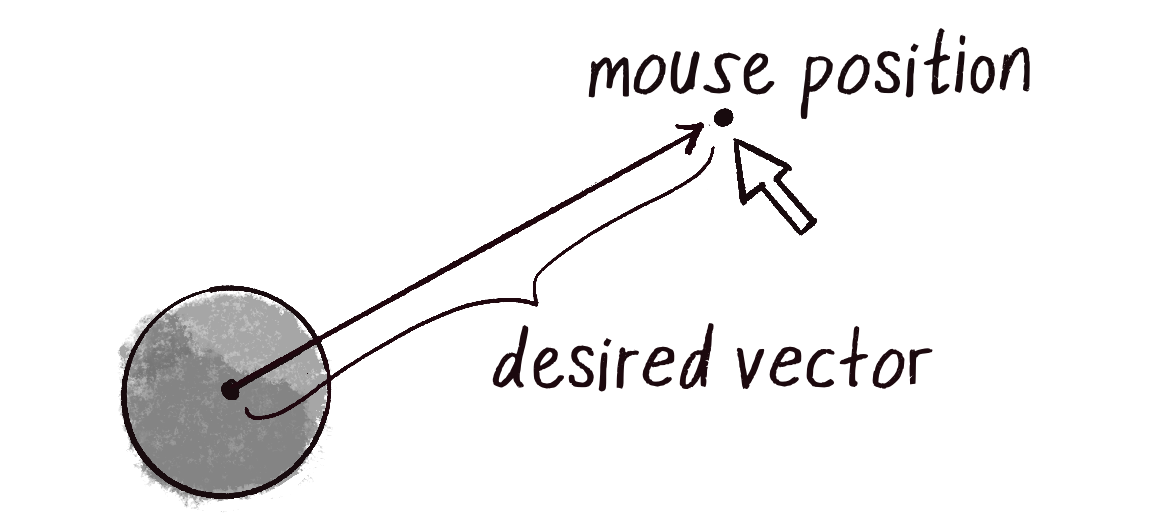

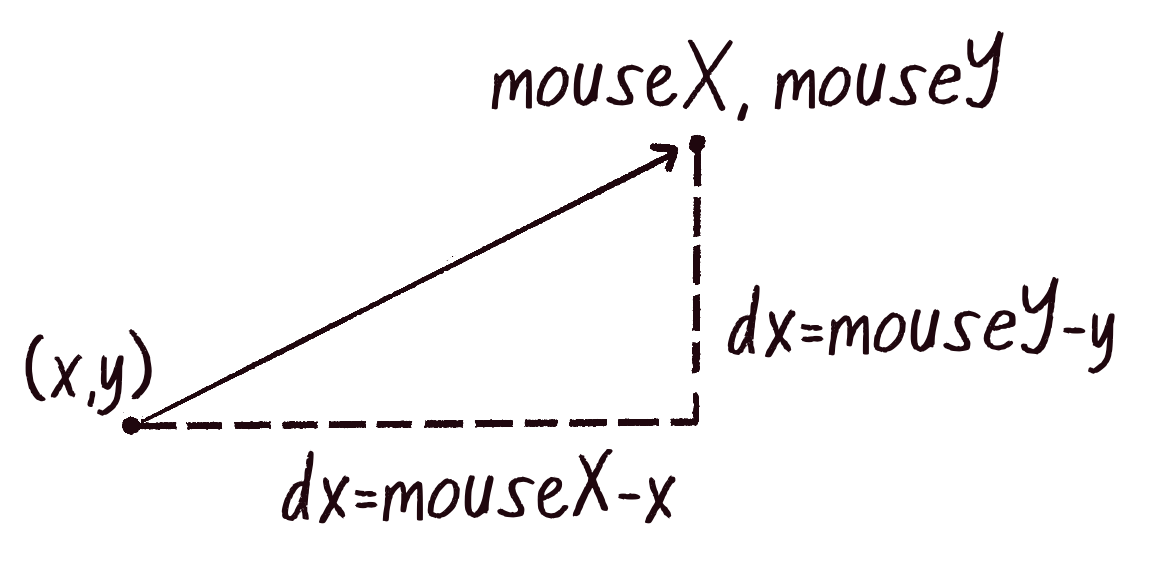

Anytime you want to calculate a vector based on a rule or a formula, you need to compute two things: magnitude and direction. I’ll start with direction. I know the acceleration vector should point from the object’s position toward the mouse position (Figure 1.15). Let’s say the object is located at the position vector (x, y) and the mouse at (mouseX, mouseY).

In Figure 1.16, you see that the acceleration vector (dx,dy) can be calculated by subtracting the object’s position from the mouse’s position.

Let’s implement that using p5.Vector syntax. Assuming the code will live inside the Mover class and thus have access to the object’s position, I can write:

let mouse = createVector(mouseX, mouseY); // Look! I’m using the static reference to sub() because I want a new p5.Vector! let direction = p5.Vector.sub(mouse, this.position);

I’ve used the static version of sub() to createI a new vector direction that points from the mover’s position to the mouse. If the object were to actually accelerate using that vector, however, it would appear instantaneously at the mouse position, since the magnitude of direction is equal to the distance between the object and the mouse. This wouldn’t make for a smooth animation, of course. The next step, therefore, is to decide how quickly the object should accelerate toward the mouse by changing the vector’s magnitude.

In order to set the magnitude (whatever it may be) of the acceleration vector, I must first ______ the vector. That’s right, you said it: normalize! If I can shrink the vector down to its unit vector (of length 1), then I can easily scale it to any other value. One multiplied by anything equals anything.

// Any number! let anything = __________________; direction.normalize(); direction.mult(anything);

To summarize, follow these steps to make the object accelerate towards the mouse:

I have a confession to make. Normalization then scaling is such a common vector operation that p5.Vector includes a function that does both, setting the magnitude of a vector to a given value with a single function call. That function is setMag().

let anything = ????? dir.setMag(anything);

In this next example, to emphasize the math, I’m going to write the code using normalize() and mult(), but this is likely the last time I‘ll do that. You‘ll find setMag() in examples going forward.

update() {

let mouse = createVector(mouseX, mouseY);

// Step 1: Compute direction

let dir = p5.Vector.sub(mouse, this.position);

// Step 2: Normalize

dir.normalize();

// Step 3: Scale

dir.mult(0.2);

//{!1} Step 4: Accelerate

this.acceleration = dir;

this.velocity.add(this.acceleration);

this.velocity.limit(this.topspeed);

this.position.add(this.velocity);

}

You may be wondering why the circle doesn’t stop when it reaches the target. It’s important to note that the object moving has no knowledge about trying to stop at a destination; it only knows where the destination’s position is.The object tries to accelerate there at a fixed rate, regardless of how far away it is. This means it will inevitably overshoot the target and have to turn around, again accelerating toward the destination, overshooting it again, and so on and so forth. Stay tuned; in later chapters, I’ll show you how to program an object to arrive at a target (slow down on approach).

Example 1.10 is remarkably close to the concept of gravitational attraction, with the object being attracted to the mouse position. In the example, however, the attraction magnitude is constant, whereas with a real-life gravitational force, the magnitude is inversely proportional to distance: the closer the object is to the attraction point, the faster it accelerates. I’ll cover gravitational attraction in more detail in the next chapter, but for now, try implementing you own version of Example 1.10 with a variable magnitude of acceleration, stronger when it’s either closer or farther away.

As mentioned in the preface, one way to use this book is to build a single project over the course of reading it, incorporating elements from each chapter as you go. One idea for this is a simulation of an ecosystem. Imagine a population of computational creatures swimming around a digital pond, interacting with each other according to various rules.

Step 1 Exercise:

Develop a set of rules for simulating the real-world behavior of a creature, such as a nervous fly, swimming fish, hopping bunny, slithering snake, and so on. Can you control the object’s motion by only manipulating the acceleration vector? Try to give the creature a personality through its behavior (rather than through its visual design, although that is, of course, worth exploring as well).

Here's an illustration to help you generate ideas about how to build an ecosystem based on the topics covered in this book. Watch how the illustration evolves as new concepts and techniques are introduced with each subsequent chapter. The goal of this book is to demonstrate algorithms and behaviors, so my examples will almost always only include a single primitive shape, such as a circle. However, I fully expect that there are creative sparks within you, and encourage you to challenge yourself with the designs of the elements you draw on the canvas. If drawing with code is new to you, the book's illustrator, Zannah Marsh, has written a helpful guide that you can find in [TBD].